Extract from an article by Lino Mancini for AltoMareBlu

Lino Mancini is an investigative journalist who has researched specific historical events of the Second World War. He was Chief Executive Officer of historic Italian firm Cabi Cattaneo for many years and is acclaimed author of the book Malta 2.

A few months ago, naval architect Franco Harrauer died with whom, belatedly, since 2011, I had the opportunity to establish a good friendship.

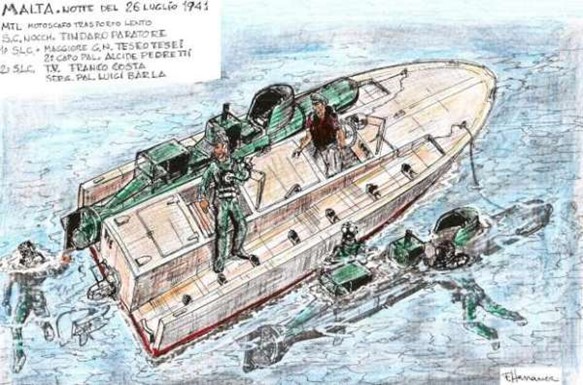

Whilst in search for images for my book Malta 2, detailing Italy’s attack of Malta’s harbors during WW2, I came across the following Harrauer print that pinpoints the beginning of events that led to the death of Teseo Tesei.

Figure 1: Malta – Night of 26 July 1941

Seeing this sketch and other articles, Harraeur described the Decima MAS personalities that he was well acquainted with during his professional career as naval architect. I was curious to contact him to hear some of these personal recollections for myself. Harraeur and I discovered that in the seventies and eighties we had followed parallel professional itineraries and on these we had continued for many years. So, precisely because they were parallel in nature, we would only get to meet at a distant point of infinity, that is, never.

But, as fate would have it, through my historical research of Malta, our trajectories diverged causing our paths to cross, and through our shared professional experiences we became fast friends.

Among Harrauer’s various short stories published on AMB, ‘Submarine Nessie’ is undoubtedly my favourite. In fact, it moved me to pay tribute to my late friend and share unpublished events that unfolded when we were on those famous parallel destinies.

In Harrauer’s story, the protagonist in question, and source of his inspiration, is revealed in stages when two SSB-type St Bartholomew torpedoes are saved in ensuing confusion and moored in a cave on Italy’s Palmaria Island, and from this cave our character was to attack one of the American merchant ships that entered the nearby port of La Spezia to unload materials for the occupying forces.

The protagonist is an SSB pilot, and we are given to understand that in April 1945, with the end of the war approaching, he heads a Special Forces Decima MAS war mission set to be his final mission.

This character and protagonist is none other than Lieutenant Sergio Pucciarini, Naval Engineer and Underwater Transport Pilot of Special Forces unit Decima MAS of the Italian Navy. Indeed, as history reveals, Pucciarini was already in the water ready to carry out a covert mission when it was abruptly stopped in its tracks by a telephone message declaring the end of the war.

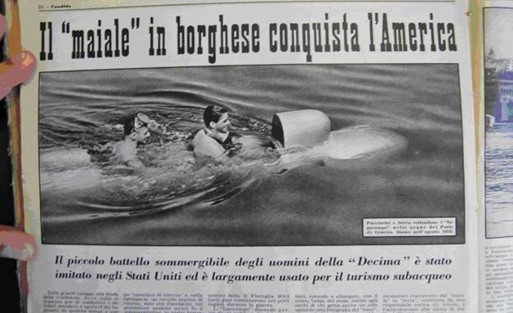

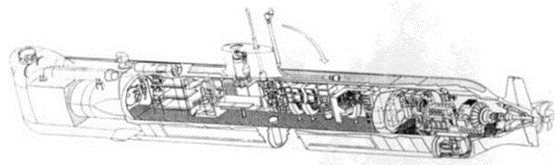

Figure 2: SSB Torpedo N °3

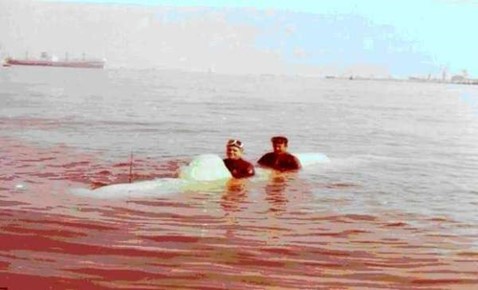

Figure 3: Batholomew Torpedo, 1945.

Preserved in the historic hall of COMSUBIN

Following the end of the war, Pucciarini and his colleague Cattaneo were the only two, among the former Decima MAS, not to renounce its technical legacy by continuing the construction of underwater vehicles. There was always the maximum of collaboration between the two because, in addition to a long-standing friendship and deep respect, an unwritten pact between them had led them to choose different paths.

This happened in 1948 when both were questioned in complete secrecy by the Navy asking if they intended to participate in the recovery and commissioning of residual SSBs.

As you know, the Peace Treaty signed in Paris on 10 February 1947 provided for the following in Article 59: ‘…No Aircraft carriers, submarines or other submersible crafts, explosive boats, or assault boats, can be purchased or built etc…’, so, any activity by SSB-type assets was therefore prevented.

The Navy, however, wanted to retain its technical heritage at all costs and therefore instructed the Captain of Vascello Notari, a former SLC pilot twice awarded the silver medal for military valor in combat, to recover all available assets and reestablish training activities.

For this purpose, a secret base in Bacoli, Naples was designated for the storage of these assets and the training of new pilots. This base remained active until the late 1960s when it was relocated to Varignano, home of COMSUBIN.

Figure 4: Naval base in Bacoli,

Naples – 1950s

Pucciarini declined the Navy’s invitation while Cattaneo joined. Pucciarini was already projected with a vision towards commercial horizons with foreign navies and did not want umbilical cords that could be a commercial constraint. He was not best thrilled, therefore, that every now and then someone from the Navy would visit on official protocol. In Livorno in 1954, Sergio Pucciarini founded COSMOS, acronym of Costruzioni Motoscafi Sottomarini meaning Construction of Motorized Subsea Crafts.

In the photo below, published by the newspaper Candido, the Hippocampus in 1954 is piloted by Pucciarini himself and Roberto Serra, another former SLC pilot of Italy’s Decima MAS who later became a renowned doctor in the international field on lung diseases.

Figure 5: Pucciarini and Serra testing ‘Maiale’ underwater vehicles,

Port of Genova – 1954

Professor Serra, now a spritely 94-year-old, recently published his book, “Orion 1943 – Last Mission of the Decima MAS Flotilla”, in which he deftly relives the historical moments that characterized his life, during 1943-1945, as an SLC-pilot, Siluro Lunga Corsa, long-range torpedoes, of the Decima MAS.

Figure 6: Pucciarini tests a CE2F-X60 in the port of Livorno – 1970s

Pucciarini was someone who in the early 1980s I had the opportunity to know during the installation and testing phases of his latest mini submarines. At that time, Pucciarini also proposed a propulsion system aboard his mini submarines that would have greatly improve underwater autonomy.

Unfortunately, the usual lack of funds and various bureaucracies did not allow us to move forward in the project at that time and hence it remained at the feasibility phase.

He was so passionate about this new generation propulsion system project that had it not been for the setbacks obstructing its production, I am convinced he would not have sold his company to foreign entrepreneurs but would have instead collaborated with the Italian Navy.

So, it was by 1989 that Pucciarini sold COSMOS to a group of Chilean entrepreneurs who led it into a crisis that culminated in the migration of all personnel and activities into DRASS, with a new ownership and rebirth.

Up until the company’s sale in 1989, Pucciarini personally directed the building of various types of SSB-type underwater vehicles, such as the hippocampus and the most famous CE2F, as well as mini submarines with a displacement of up to 120 tons. COSMOS, until the early 1990s, was also a cover for the Cabi Cattaneo because it was understood, even by foreign navies, that COSMOS provided underwater vehicles to COMSUBIN.

Figure 7: COSMOS Class 120 mini-submarine design sketch – 1990s

COSMOS products were sold to navies all over the world, and several underwater vehicles, such as the Hippocampus, were also successful in the civil field.

Figure 8: COSMOS Ce2F-X100. Latest generation electric submersible – 1990s

Figure 9: COSMOS Class 120 mini-submarine for foreign navy – 1990s

Following the takeover of COSMOS heritage, DRASS, with the advantage of being naturally open to the market and latest technologies, began a rapid modernization process – maintaining the traditional experience whilst upgrading its systems with tried and tested solutions utilized in the offshore oil and gas and commercial diving sectors.